The Pongamia Prospect

Peter McClure, chief agricultural officer for TerViva, is a longtime citrus grower on the Treasure Coast who is convinced his fellow growers’ fortunes can be revitalized by planting pongamia trees in former groves. These trees were planted five years ago and are now reaching maturity. TERVIVA

Tree from India may breathe new life into Florida’s “ghost groves”

BY ANTHONY WESTBURY

Citrus, once the undisputed king of Florida agriculture, was described recently by an official of the state Department of Citrus as “about to fall off the cliff.”

What was once a $9 billion industry, Florida’s second-most important after tourism, is in ruins. Ninety percent of the state’s groves have been infected with bacteria. In 2004 there were 7,000 groves in Florida. Today, 5,000 of those operations have disappeared, the land fallow and abandoned.

They are sometimes referred to as “ghost groves.”

Some grove owners have thrown in the towel and sold their family land for housing developments. Yet many other farmers have clung to the dream that one day citrus might return to its former glory.

Researchers have been hard at work developing disease-resistant rootstock, but progress has been heartbreakingly slow.

What’s been needed is a replacement crop that could revive growers’ fortunes. A number of alternative crops have been tried on the Treasure Coast, including biofuel plantings, blueberries, pomegranates, peaches and pineapples. Yet all have proven to have commercial shortcomings — biological or economic.

However, an answer to the citrus conundrum may be just around the corner in the form of a tree that grows wild in India, Australia and parts of Southeast Asia.

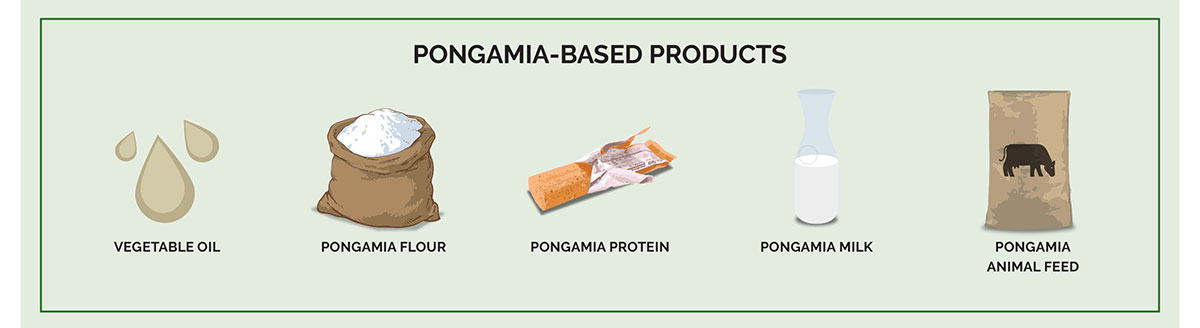

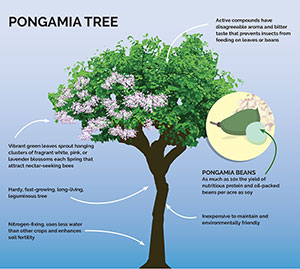

Pongamia is a tree crop with several key advantages over citrus. It grows wild in India, where its pods have traditionally been crushed to yield lamp oil. The left-over meal is often used for livestock feed or fertilizer.

Now, a 9-year-old American startup, TerViva, looks poised to revolutionize Florida agriculture by commercializing pongamia to produce a biofuel, fertilizer feedstock or food-grade commodity. TerViva officials tout the tree as a plug-in replacement for citrus. It requires little irrigation or algae-inducing fertilizer and can outperform the yield of other established crops like soy beans by up to a factor of 10.

Pongamia vegetable oil is high in oleic acid.

Pongamia products also could form the basis for what’s in great demand these days, a source of affordable plant protein. If successful, we could see pongamia used in snacks or meatless burgers.

Peter McClure is a 28-year veteran of the citrus industry who realized citrus was highly unlikely to ever recover. Currently he is chief agricultural officer for TerViva’s nursery operations in St. Lucie County, just west of Lakewood Park.

In a former citrus nursery, McClure oversees about 30 workers who are growing selected varieties of pongamia. The tree produces hundreds of variants in the wild and McClure’s task is to winnow those down to 30 or 40 “selected cultivars” that show the most commercial promise.

Actually, while the process is time-consuming, diversity in a plant product is a desirable trait, McClure said.

“Both citrus and pongamia have been around for at least 4,000 years,” he said. “The Chinese domesticated citrus by concentrating on just a handful of varieties. Unfortunately, the genetic narrowness of citrus was the reason it was wiped out by one pest. Pongamia has tremendous genetic diversity.”

One cost advantage of pongamia is the ability to mechanically harvest the crop of bean pods using mechanical harvesters originally designed to pick pistachio nuts in California. The machines shake each tree to release the pods. TERVIVA

Traditionally used for lamp oil and fertilizer, pongamia has never been used as a commercial food crop. That’s because the tree contains bitter compounds — furano flavonoids — according to Jim Astwood, TerViva’s senior vice president for products and processing.

Pongamia seed pods can be crushed to produce a high-quality cooking oil, or ground to form a high-protein flour for use in a variety of food products. TERVIVA

While the flavonoids help deter insect or grazing damage to the tree, they also have scared off wider use for food products. Astwood said TerViva has developed a proprietary process to remove the bitter compounds and is poised to supply a vast new market for plant-based, organic protein products much in demand in the 21st century.

Pongamia is a great drop-in crop in old citrus groves, McClure noted. There’s no need to modify grove beds or irrigation systems. McClure estimates pongamia should yield between 400 and 500 gallons of oil per acre — about 10 times that of crops of soy beans in Iowa that are used for ethanol production.

After oil extraction, a pongamia orchard could also produce three tons of seedcake an acre for cattle and poultry uses.

The unrefined oil can also be used as a biopesticide like neem oil.

Pongamia commercial cultivation should rival pre-canker citrus production costs of between $500 to $600 an acre, McClure said. The tree is drought- and salt-tolerant and doesn’t seem to mind standing water. It could, therefore, prove extremely valuable in areas subject to hurricane activity or where saltwater intrusion acts against other crops.

McClure, who oversees TerViva’s St. Lucie County operations, examines a seedling at the company’s Lakewood Park nursery. ANTHONY WESTBURY

The tree blooms in May and June and the seedpods containing the oil can be mechanically harvested by “shaking” machinery originally developed in California for pistachio nuts. Mechanical harvesting offers cost advantages over labor-intensive citrus, McClure pointed out.

Processing pongamia is also much more low-tech than for citrus. A simple press can extract the oil. Since 2018, Hardee County Economic Development Council has been working with TerViva to develop a permanent processing facility in Wachula. If successful, about four or five similar plants would cover most of the state’s needs, McClure said.

McClure made an interesting comparison between pongamia and citrus. Both were able to “catch the wave” of economic and social opportunity in their respective eras, he said.

Citrus rode the wave of growing post-World War II affluence in America. As more homes acquired refrigerators and freezers, coupled with the invention of frozen orange juice concentrate, OJ became an almost indispensable commodity in American homes.

Pongamia could do the same for a society clamoring for plant protein in the 21st century, particularly as Third World populations explode.

“I’ve worked in citrus all my life,” McClure said. “In fact, I was recently inducted into the Citrus Hall of Fame. So, it’s personally devastating to be part of the collapse of citrus.

“But it’s wonderful to be involved with a new crop that can be plugged in right after citrus, and to make money again.”

A nursery worker handles cuttings that are being grafted to root stock in an effort to isolate the 30 or 40 best cultivars for commercial production. ANTHONY WESTBURY

McClure noted that TerViva is working with the USDA and Nature Conservancy on best management protocols to minimize pongamia’s invasive properties. Despite being dubbed an invasive plant in Miami-Dade when it was used for ornamental purposes, McClure said the plant has been grown next to the Everglades for decades without taking over native plants.

This orchard of mature pongamia trees was planted five years ago in a former citrus grove in western St. Lucie County. Pongamia may be planted as a “plug-in” crop in old groves with very little modification needed to irrigation systems or planting beds. TERVIVA

Longtime St. Lucie County rancher Mike Adams of Adams Ranch said he had read about pongamia but mused “This is Florida, sooner or later something is going to start eating this stuff.”

Adams makes a valid point, McClure said, but he noted that in 10 years of proof-of-concept planting, the company hasn’t had to spray to control pests. Moreover, he said, deer, cattle, horses and pigs won’t eat the plant because of those bitter compounds.

McClure sees pongamia as a home-run in supplying organic feed, most of which currently is imported. Pongamia offers the promise of a U.S.-grown, verifiably organic protein product.

Can you say “Impossible Burgers”?

TerViva is scaling up pongamia cultivation. Commercial grower Evans Properties planted a five-acre orchard about five years ago in western St. Lucie County that is now reaching maturity.

Evans is expanding the concept on former citrus grove land at State Road 70 and Header Canal Road. Pongamia saplings on that site are now one year old, and the company plans to plant 500 acres in the future.

Astwood, TerViva’s food science expert, said there has been a lot of interest in food-grade products made from pongamia. It’s a non-GMO product that contains high levels of healthy Omega-9 fatty acids and it’s low in saturated fats.

Potential customers include Mondelez International, a food conglomerate which includes Nabisco, Cadbury, Ritz, Velveeta and Oreo brands in its portfolio, Astwood said.

Ron Edwards of Evans Properties likes what he sees so far from pongamia.

TERVIVA

“We were one of the first ones to plant pongamia as an alternative crop to citrus,” Edwards recalled. “With greening, we were very concerned it could become an existential threat and we quit planting new trees until a cure was found. We began looking at alternatives and built a 300-acre research farm to investigate biofuels, energy crops, castor oil — things that had relatively high outputs per acre.”

Edwards said they met with TerViva in 2011 to 2012 when they were looking for test lots. They planted from seed at Bluefield and started the Header Canal project.

“The longer we grew them the more convinced we were that this could work.”

Edwards reeled off pongamia’s advantages: no need for spraying, little fertilization required, natural defense against animals and insects. So far, pongamia has proved to be a true plug-in crop, Edwards said, with only minor modifications of old citrus planting beds needed to aid mechanical harvesting.

Pongamia trees produce as much as 10x the beans per acre as soybeans. TERVIVA

“We’re now ramping up propagation production (to determine which are the best cultivars), tripling and quadrupling our (nursery) capacity.

“For growers to plant at a commercial scale, they have to be confident it is problem-free and also to the end users of food products. I think it’ll be more profitable than citrus. It’s carbon-neutral and you won’t have to tear down the Amazon (rain forest) to plant soy beans. It will have a lot less environmental impact.”

So, finally, we may have a viable commercial alternative to citrus in Florida.

Pongamia seems to be a crop with plenty of pluses and few negatives. Now approaching its second decade of planting on the Treasure Coast, growers like Edwards report very little downside to the product.

If it is a commercial success, pongamia grown here could form the basis for salad dressings, sauces and food products, frying oils and even meat alternatives.

And that would be sweet indeed.

Treasure Coast Business is a news service and magazine published in print, via e-newsletter and online at tcbusiness.com by Indian River Magazine Inc. For more information or to report news email staff@tcbusiness.com