Once king, agriculture making comeback on Treasure Coast

It’s hot work as riders move calves at the Pearce Cattle Company Ranch in Okeechobee County, the largest cattle county in Florida. PEARCE CATTLE CO.

Unlikely to regain previous status, but citrus on rebound

BY BERNIE WOODALL

Agriculture has been a prime driver for the Treasure Coast economy for most of its modern history. More than a century ago, pineapples were the top crop. Pineapples were eventually replaced by other crops, particularly citrus, which along with cattle ranching continued to dominate the economic landscape until air conditioning and interstate highways helped boost tourism and industries tied to exponential population growth, including home construction.

Now, industries tied to healthcare and retail businesses are the biggest employers, each with about 26,000 workers in Indian River and St. Lucie counties, and retail is tops in annual revenue at about $6.83 billion, according to data compiled by FPL.

A tub of harvested oranges waits to be loaded in an area citrus grove. Indian River citrus has been shipped around the globe. FLORIDA DEPT. OF CITRUS

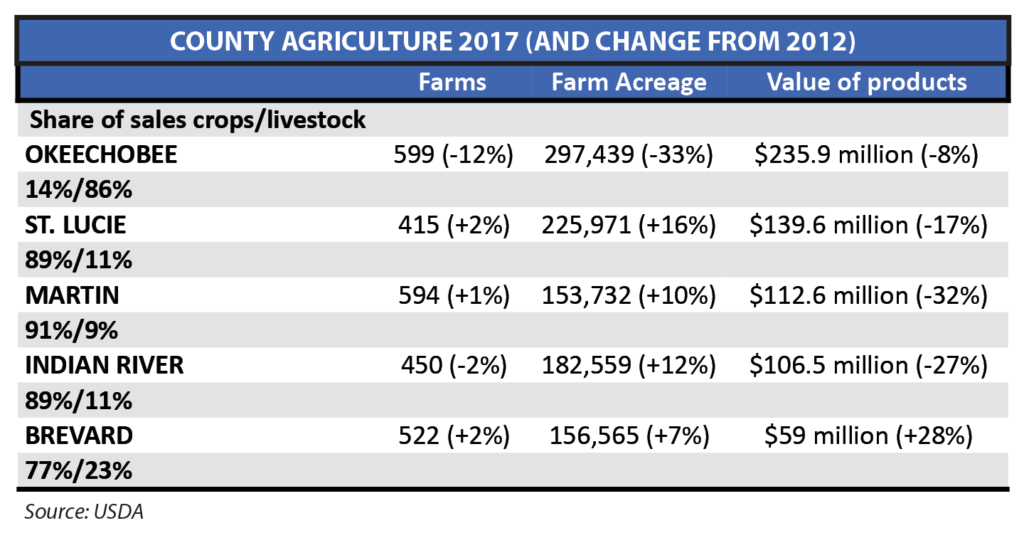

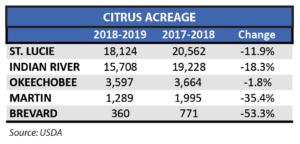

Agriculture still plays a key role in St. Lucie, Indian River, Martin and Okeechobee counties. Citrus in the area three decades ago was a $2.1 billion industry but it is a third that size now, said Doug Bournique, executive vice president of the Indian River Citrus League. Citrus is making a mild comeback after being ravaged by tree diseases while the cattle ranching industry is finding ways to survive against its major enemy — development.

Packing house workers sort grapefruit as the fruit moves along on a conveyor belt. FLORIDA DEPT. OF CITRUS

Citrus farming in Florida has been threatened by freezing winter temperatures since the first grove of oranges was planted in 1807 on what is now Merritt Island in Brevard County. However, the primary killers of citrus groves have been disease. Citrus canker in the 1990s was followed about 15 years ago by the citrus greening disease. St. Lucie, seventh in the state in volume of citrus grown, and Indian River, eighth, have what’s left of the citrus industry in the area.

“Its impact has been devastating to our industry,” said Bournique of citrus greening. In the late 1990s, Florida had about 950,000 acres of commercial citrus, and now there is less than half that. In December, chairman of the Florida Senate agriculture committee, Ben Albritton, said the state’s citrus industry was “standing pretty close to a cliff.” Albritton’s district includes all or parts of seven counties, including Okeechobee.

“In 1998-1999, the Indian River District alone had 40 packing houses, and now we have six,” said Bournique. “The number of growers in the Indian River Citrus League was about 1,600, and now it is about 250.’’

Still, the U.S. Department of Agriculture forecast in December that for the 2019-2020 season, Florida will produce about 80 million boxes of citrus, up 3.3 percent from the previous season.

“Five years ago, I looked at the research and I didn’t see any hope at all,” Bournique said. “I thought we’d milk out the life of these trees and that would be it. I know we’re going to succeed now.”

New groves are being planted in the Indian River area on a scale not seen in years, he said, even if the industry is a shadow of its former self.

That’s largely because of progress toward overcoming citrus greening disease that has been achieved by researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the University of Florida.

Bournique’s office in Fort Pierce is now alongside researchers so he can keep up with advances to fight citrus greening. “I talk to the 50 PhDs and 150 lab techs that are here, and we live and breathe it,” he said.

Bournique’s office in Fort Pierce is now alongside researchers so he can keep up with advances to fight citrus greening. “I talk to the 50 PhDs and 150 lab techs that are here, and we live and breathe it,” he said.

Total fruit sales, dominated by citrus, accounts for 65 percent of agricultural product sales in St. Lucie, and makes up 82 percent of agricultural product sales in Indian River, the USDA reports.

USDA figures show that Martin County’s top crops are plant nurseries and sod farms at $45.3 million in 2017, and sugarcane, with sales of $12.3 million.

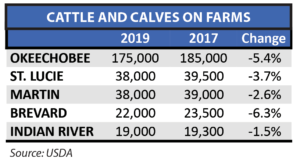

While citrus dominates the agricultural industry in St. Lucie and Indian River counties, raising cattle is by far the leader in Okeechobee County.

Just as in decades past, cowboys and their dogs move cattle at the Pearce Cattle Company Ranch in Okeechobee County, a multi-generational cattle operation. PEARCE CATTLE CO.

Okeechobee tops the Treasure Coast in sales of agricultural products at $235.9 million in 2017, the USDA said. Of that total, 86 percent comes from livestock. With a headcount of 175,000 cattle and calves at the start of 2019, Okeechobee is the largest cattle county in Florida, which the industry publication Beef Market Central says is 12th in the nation in the number of beef cattle. In Okeechobee County, slightly less than half the cattle, 81,000, are beef cows and calves.

Okeechobee tops the Treasure Coast in sales of agricultural products at $235.9 million in 2017, the USDA said. Of that total, 86 percent comes from livestock. With a headcount of 175,000 cattle and calves at the start of 2019, Okeechobee is the largest cattle county in Florida, which the industry publication Beef Market Central says is 12th in the nation in the number of beef cattle. In Okeechobee County, slightly less than half the cattle, 81,000, are beef cows and calves.

Matt Pearce is a seventh-generation cattle rancher in Okeechobee, the president of Pearce Cattle Company and the president of the Florida Cattleman’s Association.

Pearce said the peak of the cattle industry on the Treasure Coast and Florida was probably from 2000 to 2008. Mike Adams, president of Adams Ranch Inc. based in St. Lucie County, said the peak may have been the 1980s as much as the early 2000s.

Tending the herd in Okeechobee, Florida’s top cattle county. PEARCE CATTLE CO.

While tree diseases endanger orange and grapefruit groves, cattle ranchers on the Treasure Coast and across southern and central Florida often lose their land to development, Pearce and Adams each said.

“Some developers tell me that the area from Palm Beach County to Fort Myers is all going to be filled in eventually,” Pearce said. “And there will be one solid development from Orlando to Tampa.”

He said that developers like the land that has been grazed upon by cattle, because of the relatively low-impact and “nearly pristine” nature of ranchland including its hammocks and ponds and sloughs.

“That’s where people want to live,” Pearce said. “We’re losing more ranchland every day” in south and central Florida.

In Florida, Pearce said, cattle ranching means birthing calves in October and November to be ready by spring, the prime time for grass grazing, brought up to 500 to 700 pounds and shipped to feedlots in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Colorado where they grow to about 1,250 or 1,300 pounds before being slaughtered and sent to meat processing plants.

In 2008, Pearce said, Okeechobee County had 90,000 beef cattle compared with 82,000 a decade later.

St. Lucie County had a headcount of beef cattle in 2008 of 27,000 and 28,000 in 2018, Pearce said, and Indian River’s beef cattle totaled 15,000 in 2008, and dropped to 12,800 in 2018.

Treasure Coast Business is a news service and magazine published in print, via e-newsletter and online at tcbusiness.com by Indian River Magazine Inc. For more information or to report news email staff@tcbusiness.com